Why Everyone Should Celebrate Black History

by Matt Martin, Pastor at Veritas Community Church

Why Ask, ‘Why Black History?’

Each year as Black History Month unfolds it seems one inevitable question arises, “Why is there a Black History Month, and how come there’s no White History Month?” One of my initial reactions to this question is to point out that history is, as Winston Churchill once noted, “written by the victors.” What this suggests is that the perspective from which much of our history is told is that of White people, and even more specifically, White men. Indeed, the whole idea of how we should interpret history and how we should decide which sources are credible is up in the air in many state legislatures right now, as any AP history curricula that reflects poorly on the United States is being scrutinized.1 I can’t help but see the similarities between suspicion of ‘Black History’ and the recent backlash surrounding the ‘black lives matter’ hashtag in the wake of the Michael Brown shooting in Ferguson, Missouri. All of it seems to substantiate what Robin DiAngelo refers to as ‘White Fragility’, a term she uses to refer to the low tolerance for racial tension that Whites in North America have developed through being part of an insulated and protected majority.2

I believe that this ‘fragility’, and these types of debates inhibit us all from having deeper dialogue and appreciation for one another, and more importantly, for the Kingdom of worshippers that God is redeeming for himself. What I mean to suggest is that if we are to reflect the Kingdom of God on earth in our longing to be part of a “ransomed people for God from every tribe and language and people and nation”3, then we should joyfully embrace a holistic understanding of our past which allows us to celebrate and embody the beauty and dignity with which God created all of humanity. So what might this look like?

Why I Minored in African & African American Studies

When I was an undergraduate studying public affairs at Wright State University, I began taking a series of duel-degree courses that focused on the history of theology and racism in America. Although I had initially intended to minor in Religion, I found that what really intrigued me about these courses was the African American perspective on history, which led me to complete my minor in African and African American Studies (AAS) instead. As a White male I was an anomaly in the AAS program; Black classmates were understandably curious and skeptical, some of my White friends casually joked about it, and years later my father described it as “surprising”. When I reflect on why I took those courses, I realize that it wasn’t primarily out of a sense of White guilt, although that’s certainly something of which Whites need to be ever-conscious. Rather, I simply found the material interesting, compelling, educational, and even transformative, with the most important lesson being that history and the present are experienced differently, and sometimes what is perceived as good or right by one group of people is actually evil and ugly.

We don’t have to go directly to Black History to see examples of this that seem to resonate more readily. Studies of the Eugenics Movement, World War II, Hitler’s rise to power, Nazi propaganda and the Holocaust clearly demonstrate how differently events can be interpreted and re-interpreted retrospectively, and thus show the importance of considering a variety of perspectives. We can learn a lot from history, and we can learn a lot from different eyes and voices. This is why can learn a lot from Black History too. It’s a history full of struggle, desperation, injustice, and despair…yet also of survival, resilience, grace, and of beauty and strength in the face of oppression—isn’t that worth learning from?

A Case Study on Learning From Black History

As a small case in point, I want to draw attention to an issue that Veritas is considering as we think about how best to love and serve the city and the neighborhoods near which our congregations gather. One very significant problem in Columbus and other cities across the country is residential segregation. Racially diverse, mixed-income neighborhoods are like the Holy Grail for city leaders everywhere, and it’s a tremendous challenge developing them in the context of current housing and credit markets. This is why it seems so strange when a house in Italian Village sells for a half-million dollars, while only two blocks away, in Weinland Park, there are much more modest homes and even a variety of subsidized units. It’s certainly a puzzling aberration in our society, but only because of the ways privilege has influenced our markets, planning and zoning laws. As a result, communities now have to intentionally pursue and maintain mixed-income neighborhoods through creative and often obscure means like various tax credits, blends of subsidies and vouchers, non-profit community development efforts, and housing trust funds.

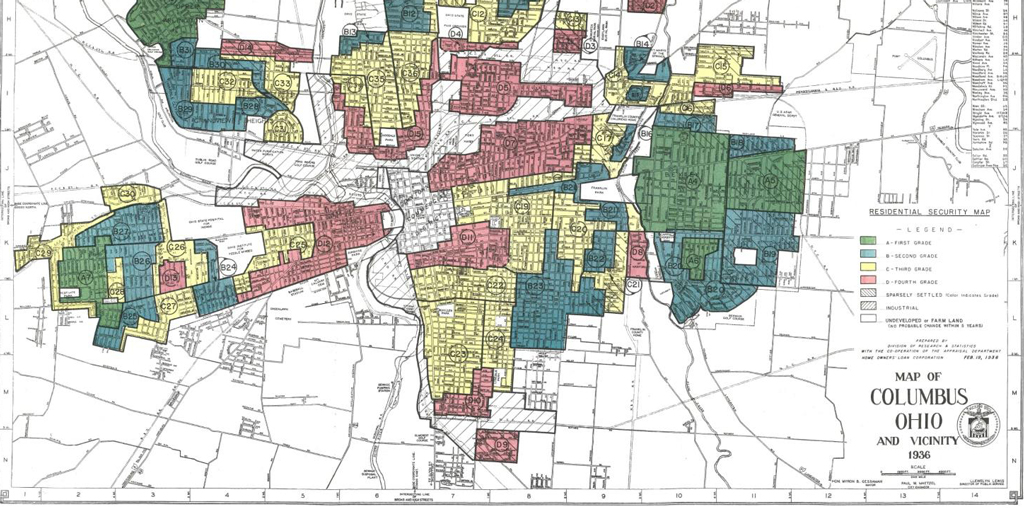

Figure 1. The 1936 Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Map of Columbus, Ohio. More commonly referred to as ‘Redlining’ maps, these were largely based on racial bias, and were used to designate which neighborhoods were eligible for federal mortgage insurance, and which were not.

However, there was a time when communities lived in such economic diversity—in Black neighborhoods like Columbus’ Near East Side prior to the 1970s. Why and how, one might ask? Ironically, it was the effects of discrimination in housing and mortgage markets that forced this upon Black neighborhoods, through racial zoning, race-restrictive covenants, racial steering, and blockbusting. ‘Redlining’, perhaps the most devastating and widespread among these discriminatory practices, was a racially-informed housing finance policy that carved deep race and class divides into the landscape of nearly 300 cities and had a multi-generational impact on family wealth creation4. These practices resulted in, among other things, affluent Black doctors, bankers, and shop-keepers living next to plumbers, railroad workers, and housekeepers of more modest incomes because none of them could live elsewhere. This is admittedly a complex history because economic integration was achieved through such unfair means, and also at the expense of racial diversity. Today, many older Black folks who grew up in those neighborhoods continue to cherish their memories of a genuine, dignified sense of community, even while they lament the host of atrocities which also marked that era. Although legislation like the Fair Housing Act of 1968 opened up new possibilities for integration, it may have also contributed to new challenges in historically Black neighborhoods, where concentrations of less economically-mobile residents began to take shape following the 1960s.

As we work to improve the neighborhood fabric of our cities, we could learn from this history and invent new tools to make the housing markets both economically and racially diverse in ways that lead to better communities for everyone. But we can’t learn from what we don’t study, or what we don’t teach in our schools.

Black History Matters

Black history is important and offers many lessons for everyone. Moreover, Black history is American history, and not merely some alternative rendering of it. The song “We Shall Overcome” is one that became an anthem of the American Civil Rights Movement, and is thought to be based on an old hymn that was written by a Black pastor named Charles Albert Tindley, who was born before the Emancipation of slavery and became known as “The Prince of Preachers” (C.H. Spurgeon wasn’t the only one). It is truly amazing and inspiring to see what Black people have overcome—and what they have invented, built, and contributed to American life and culture. In so doing Black people represent a significant part of our collective story of grace—a story we must all embrace. Our stories are intertwined; they have been since God made us in his image, and they will be as he establishes one new people for himself through Jesus for all eternity.

What Next?

One logical question to ask is, “where do we go from here?” God’s coming Kingdom is one thing, but how can we begin to reflect that today? What does it look like to experience God’s reconciliatory power in view of our past and present circumstances? Here are a few practical next steps for moving forward:

1. Examine your life and your heart. Consider your life experiences and the things that have shaped your views on race and class. Begin to recognize this as a Gospel issue and a discipleship issue rather than just a societal or church-wide issue. This isn’t just a cultural fad; these are spiritual matters that cannot be redeemed through education alone.

2. Pursue a person of color at church, work, school, or in your neighborhood and listen to their story. Push through the awkwardness and see through new eyes. Acknowledge how our brothers and sisters in Christ from non-White cultures do not have the luxury of forgetting about this history, and that part of being in the family of God means bearing one another’s burdens.

3. Engage your community group in a dialogue about these issues and why they matter.

4. Attend the Yaves concert this Saturday at Veritas to help support local families, and hear some music that perhaps you’ve overlooked in the past.

4. Read some of the references cited in this article, or books like The Souls of Black Folk, by W.E.B. Dubois, The Miseducation of the Negro, by Carter G. Woodson, or The New Jim Crow, by Michelle Alexander, just to name a few.

5. Consider attending this upcoming conference on The Gospel and Racial Reconciliation with some of the leaders and pastors from Veritas. If you’re unable to join, check out the writings of some of the speakers from the conference.

7. Be intentional about getting out of your comfort zone by attending a local event or venue where you might not be part of the racial majority. Listen, be wise, be respectful, be receptive.

Comments are closed.